What to Know

- Allies of former President Donald Trump formed Defend Florida to challenge the integrity of the state’s elections. The group went door to door to find “invalid” voter registrations.

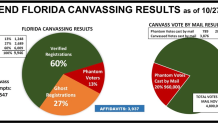

- Defend Florida said that 13% of 9,946 voters were “phantom voters,” which it defined as ballots cast by a person who is deceased, did not live at the address or the address isn’t a residential address. The group then extrapolated that number to claim 1.4 million ballots cast during the 2020 presidential election were by “phantom voters.”

- Election officials and experts say that Defend Florida’s methodology is amateurish and flawed.

Republican operative Roger Stone is among the supporters of former President Donald Trump who want an "audit" of Florida election results even though Trump won there.

"If Florida Governor Ron DeSantis does not order an audit of the 2020 election to expose the fact that there are over 1 million phantom voters on the Florida rolls in the Sunshine State I may be forced to seek the Libertarian party nomination for governor (of) Florida in 2022," Stone said on Oct. 31 on Gab, a social media platform for conservatives.

Get South Florida local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC South Florida newsletters.

Stone told us in a text message that he was referring to the findings by Defend Florida, a group connected to a national group of Trump allies, Defend Our Union, formed after the 2020 election.

But experts on election administration say the group’s methodology and conclusions are flawed.

Defend Florida members went door to door to look for "phantom votes" cast by people who are deceased, did not live at their listed addresses or else had listed addresses that weren’t residential. They also came up with a number of what they called "ghost registrations" held by people who are dead or had similarly problematic addresses.

"There is no such term as a ‘phantom voter’ or ‘ghost registration,’" said Thessalia Merivaki, a political scientist at Mississippi State University. "These seem made up and aimed to sensationalize the voter list maintenance process."

Stone, who advised Trump early in his 2016 presidential campaign, was convicted in 2019 on several counts that involved lying to Congress about the 2016 election. Trump commuted Stone’s sentence in July 2020 and then pardoned him in December.

Stone’s push for an "audit" of Florida’s election is in spite of the fact that Trump won the state by about 372,000 votes, or 3 percentage points.

And not many Republican leaders in Florida share Stone’s view on the need for an audit. After the 2020 election, DeSantis called Florida a model for the rest of the nation and in October said that the state election audits "passed with flying colors." Florida’s secretary of state, a DeSantis appointee, told the Tampa Bay Times the vote tally was "accurate, transparent, and conducted in compliance with Florida law."

Election experts criticize methodology used by group counting "phantom voters."

This summer, Defend Florida searched for invalid registrations, knocking on doors and combing state data, the Tampa Bay Times found. "What method did you use to vote in the last election?" they said they asked the voters they encountered. "Did you receive any extra ballots in the mail?"

The group said that as of Oct. 27, it attempted to contact 18,547 registered voters and successfully gathered information on 9,946. Defend Florida said it found that 13% were "phantom voters" — ballots cast by deceased people, folks who did not live at the address listed or else had addresses that weren’t residential.

Defend Florida extrapolated based on those findings and said that of the 11.1 million Florida votes cast in November 2020 there were about 1.4 million "phantom votes." That’s what the group’s website showed when we accessed it Nov. 1.

Caroline Wetherington, a co-founder of Defend Florida and Trump supporter, directed us to a statement on the organization’s website that says that the majority of "phantom votes" were cast by mail.

Merivaki and fellow political science professor Barry Burden at the University of Wisconsin-Madison both told PolitiFact they found flaws with the group’s methodology.

"The main problem is that the canvassers are visiting residences up to a year after the election," Burden said. "Even if the voter file was perfectly accurate on Election Day 2020, things would have changed since then. People move, die, and change their names."

The second problem is that Defend Florida doesn’t explain how it chose the 31 counties or the areas where they canvassed. When we asked Wetherington for specifics, her response provided no additional insight: "We canvassed homes of registered voters and obtained the status of 9,946 registered voters. Some voted in the 2020 election and some did not."

County election supervisors say activists don’t understand election administration

Election supervisors who have been contacted by Defend Florida said they feel the activists don’t understand how election laws work.

Brian Corley, Pasco County’s supervisor of elections, in August received a letter from the group that read, in part, "We are calling on you to clean your voter rolls immediately of those voters who have not voted in 8 years."

Corley asked them to provide the specific voter information but said he didn’t get a response.

Election officials can’t remove someone from voter rolls for simply not voting. Citizens have a right not to vote, as many do in every election, said Marion County Supervisor of Elections Wesley Wilcox, a Republican who also serves as president of the Florida Supervisors of Elections.

There are specific criteria in election laws that explain when a voter can be removed. If a mailing is sent to a voter and returned undeliverable, the voter becomes inactive. If the voter is inactive for two federal election cycles, then the voter becomes ineligible.

County election officials regularly receive data about deaths and felony convictions from state offices which they use to update their voter rolls. Florida is also a member of ERIC, a consortium of states that share data to help each other remove voters who have died or moved.

Mike Bennett, supervisor of elections in Manatee County and also a Republican, said the group’s information is "completely unreliable" and said "the whole thing is pretty phony."

In response to news reports about citizens calling for audits, the Florida Supervisors of Elections issued an October statement defending the integrity of Florida’s elections.

Election officials take multiple steps to protect the integrity of voting such as verifying voters’ signatures on mail ballots and checking IDs for in-person voters. Florida law requires that all votes are cast on paper ballots and counted on certified machines that have been publicly tested. After the election, officials conduct a public audit to verify results.

Election supervisors told us that the steps they take work, and pointed to isolated examples of attempts of voter fraud. Last year a Bradenton man was arrested after officials found he tried to obtain a mail ballot on behalf of his dead wife.

"It’s not the kind of fraud people are worried about turning over a presidential election," Bennett said. "His excuse was that he was ‘testing our system.’ He got caught."

One final note before we rate Stone’s statement about "phantom voters."

Stone, who is currently a registered Republican in Fort Lauderdale, said in his Gab post that if he runs for governor in 2022 he would run as a Libertarian. But state law says that a candidate must be a registered member of the party for which he or she is seeking nomination for one year before the start of the qualifying period.

The qualifying period begins June 13, 2022, for the governor’s race.

Our ruling

Stone said, "There are over 1 million phantom voters on the Florida voter rolls."

This is an unsupported claim aimed at discrediting the state’s election administration. Stone is drawing from findings by Defend Florida, a group of Trump-aligned citizens who have gone door to door in search of what they say are invalid voter registrations. While the group has shared some details of its data collection process and findings, it has been opaque about its methodology.

What it has shared suggests the group has tested only a small sample of Florida voters. Their finding also ignores that people inevitably relocate and that there are rules that govern when people can be removed from voter rolls.

Election officials take multiple steps to make sure voters are eligible to cast ballots, including that they are not dead. The statewide election officials association, which represents officials from both parties, as well as state officials have publicly said that Florida’s election was transparent and secure.

We rate this statement Pants on Fire!