What to Know

- Data from the CDC suggests that minority groups are getting infected with the novel coronavirus at disproportionally high rates

- Black people and Latinos often fare worse economically and can face significant barriers in accessing reliable healthcare

- Experts say that due to poor testing and other factors, the real impact of the pandemic on minority groups has yet to be fully accounted for

It has been suggested that COVID-19 does not discriminate, but some experts say that the numbers show a different story.

The virus, which researchers have confirmed originated in the Wuhan region of China last winter, has sickened people across every demographic and almost every country around the globe; government and medical authorities have urged people of all ages, races, ethnicities and economic backgrounds to beware.

But as data about the virus's victims continues to emerge, experts are pointing out how certain communities have been more severely affected than others in terms of number of deaths and infections.

“If America is literally in a war with coronavirus, let’s just be honest and say that the African-American community, as well as our Hispanic community, has been ambushed," said Dr. Kevin Jenkins, Ph.D., of the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion (CHERP) at the Corporal Crescenz VA Medical Center in Philadelphia.

At the beginning of April, the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, acknowledged the disproportionate impact the novel coronavirus was having on African American communities.

While figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are limited— of 1,062,446 confirmed cases, only 44.5% of individuals specified race— the demographic data that is available suggests certain groups are falling ill at disproportionately high rates.

Local

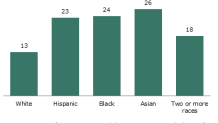

Of the cases for which individuals did specify race, 28.8% are Black as of May 1st, even though black people only make up 13.5% of the U.S.'s total population (according to the latest figures from the U.S. Census Bureau).

Similarly, while Hispanic/Latinos only make up 18.3% of the total population, they represent 25.4% of all coronavirus cases for which ethnicity was specified as of May 1st.

Hispanics: language, healthcare and other barriers

Veronica Robleto of Florida Legal Services told NBC 6 the U.S.'s Hispanic population is vulnerable due to a combination of reasons, such as the language barrier many immigrants face.

Florida Legal Services recently collaborated with the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Rural Women’s Health Project and 40 other immigrant rights organizations in a letter to Governor Ron DeSantis demanding that federally-funded emergency resources be made available to limited English proficiency individuals.

Robleto pointed out that most government websites addressing the health crisis publish translated information in hard-to-find places like the bottom of their web pages.

In some rural areas of Florida, where many Hispanics work in the agriculture industry, press conferences given by their local leaders or the governor are rarely translated, making official information and resources related to the coronavirus nearly impossible to access.

By failing to do, Robleto mentioned, the government is in violation of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which states federal actors cannot discriminate based on national origin. Robleto says that limited English proficiency is included in that category.

“The community organizations have stepped up to provide this information, but it really is the responsibility of the government to follow the law and get this information out to everyone,” Robleto said.

The living conditions of minority populations in the United States may contribute to underlying health problems and to limited access to proper medical testing, diagnosis and treatment, even in the absence of a pandemic.

COVID-19 only highlights the already existing challenges that put the U.S. Black and Hispanic community in more peril. Among the difficulties, these groups are more likely to live in multi-generational households than are white families, according to Pew Research Center.

This makes self-isolating during the pandemic a virtually impossible act, and places the elderly at a higher risk; minorities also more frequently live in densely populated areas.

"People of color are more likely to live in densely packed areas and in multigenerational housing situations, which create higher risk for spread of highly contagious disease like COVID-19," said U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams at a White House briefing in April.

In addition, undocumented immigrants shy away from seeing a doctor for fear they will be discovered and deported. This too precludes many Hispanics from seeking adequate treatment.

These communities are also more likely to have low incomes. A recent survey from Pew Research Center suggests that lower-income adults are being impacted more severely by the pandemic's economic fallout.

Blacks and Hispanics are also less likely to have health insurance, according to most recent figures from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The risks that come with being an essential worker

Robleto noted that many of the non-English speakers and minority groups make up a huge portion of the essential workers who, in spite of being among the lowest-paid, have continued to work during the pandemic.

“They have continued to pick our vegetables, clean the hospitals and work in restaurants that are doing take-out," she said.

"This is a huge part of people that are taking care of our society as a whole. So we need to take care of them as well," Robleto added.

Dr. Zackary Berger, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins division of general internal medicine, claims that COVID-19 cases and deaths are being significantly undercounted due to the obstacles these minority groups face.

“If you live 6-8 people to an apartment, as so many of my Hispanic patients do in Baltimore, you have to go to work because you have to eat," he said. "And you have no workplace protection, you have no access to healthcare because you’re not insured, and you don’t have any money."

Dr. Berger is a staff physician at the Esperanza Health Center, a free clinic in Baltimore serving primarily undocumented Spanish-speaking immigrants.

He told NBC 6 that the U.S.'s political and economic systems have historically failed to take Black, Hispanic, homeless and trans communities into account, and "that's happening now with COVID."

Back in Philadelphia, Dr. Jenkins said he has noticed the same situation, adding that there is a myth that the Black community is uninformed about issues surrounding COVID-19.

He has gotten many emails and messages on social media from patients in disadvantaged communities alleging they are being dismissed by medical professionals in spite of expressing concern and demonstrating COVID-19 symptoms.

Dr. Berger believes the solution involves finding out what these communities' needs are. “You can’t ask people to stay home, if their landlords are kicking them out on the street, and you can’t ask people to get medications to treat their illness and stay home if they don’t have money for those medications,” he said.

Robleto said that addressing these healthcare failures is not just altruistic for the short term; rather, it is in everyone’s best interest in the long run.

“It’s not only about equity, and what’s fair for these individuals," she said, "but if they’re not getting treatment and tests, it’s going to affect everyone."