They’re out there.

In the deep blue waters, miles off the beach, there is a watery highway. It’s like the Atlantic Ocean’s version of Interstate 95 with lanes heading north and south.

But instead of cars and trucks, fish and turtles of all shapes and species and sizes use the warm currents of the Gulf Stream and its eddies as a way to commute more than a thousand miles each season.

One of those annual commuters is the fearsome, mysterious great white shark.

The Hurricane season is on. Our meteorologists are ready. Sign up for the NBC 6 Weather newsletter to get the latest forecast in your inbox.

WELCOME TO THE TROPICS, SABLE

When Vero Beach was founded in 1919, its founders coined the slogan, “Where the tropics begin.” Fitting, since a cold day here is about as rare as a cold in, well, you know where.

For over a century, Vero Beach and the Treasure Coast have drawn an ever-growing population of winter visitors escaping the frigid North. But for many millennia, birds, fish and even sharks have also come to Florida to escape freezing wintertime temperatures.

Local

The latest arrival is a great white shark named Sable. At 7:47 p.m. on Jan. 23, Sable sent up a “ping” from the satellite tag affixed to her dorsal fin. It meant the dorsal broke the surface of the water.

Beachgoers have nothing to worry about — well, probably not. Sable may be 11.5 feet long, weigh over 800 pounds and have a mouthful of hundreds of razor sharp teeth, but she is nowhere near the beach, at least not where she last pinged. She was an estimated 20 miles offshore, traveling along the edge of the Continental Shelf, where water depths are over 300 feet. She has traveled over 2,500 miles since being tagged.

MEET SABLE

So what do we know about Sable? Well, she likes long swims, tuna sashimi and loves music by The Weeknd.

Seriously, when the team from OCEARCH first met Sable, it was two hours before dawn in the cool autumn waters off the coast of Nova Scotia. Sable took a bait, and before she knew what was going on, she found herself being lifted up from below by a hydraulic lift on the OCEARCH research vessel.

The research team took length and weight measurements, blood samples and checked other vital signs. In 15 short minutes, the team can collect 12 different biological samples from the shark. The team then affixed a smart position or temperature (SPOT) tag on the dorsal fin and lowered the shark elevator (platform) back into the water.

“Sable is the 76th shark sampled, tagged and released in the nonprofit research organization’s Northwest Atlantic White Shark Study and the third of Expedition Nova Scotia 2021,” according to OCEARCH’s website. “She was named after the Sable Island National Park Reserve, located approximately 180 miles offshore of Halifax, Nova Scotia, near where she was tagged” in 2021.

OCEARCH began in 2007 and has hosted 200 scientists who have helped execute 42 expeditions and tagged over 431 animals. The organization performs:

— Full health assessments of each shark

— Microbiological studies

— Microplastic-associated toxin exposure

— Movement, temperature and depth studies through the use of 3 different tags.

A COMMON OCCURRENCE?

Great white shark sightings in the waters along eastern Florida have become increasingly common in recent years. Bob Hueter, OCEARCH chief scientist, of Sarasota, was on the mission when Sable was tagged.

“At her size, she’s probably starting to approach sexual maturity, and if not, she will be in a few years or so. She spent a couple of months cruising around Canadian waters feeding on high energy food like seals before she started coming south in the early part of the winter,” Hueter told TCPalm.

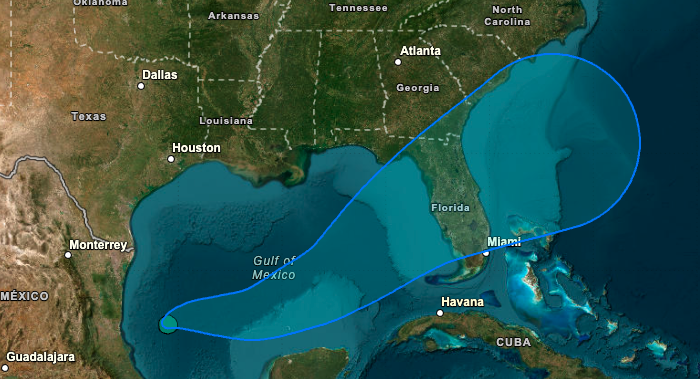

“If you follow her track you can see she pretty much made a steady progression down the coast, maybe lingered around Cape Hatteras a little bit.”

Hueter said when the white sharks come south, they can’t feed on seals. But they may find whale carcasses, feed on other sharks or on certain kinds of fish. Possibly blackfin tuna, bonito (little tunny) or other fish they can catch along the edges of the Gulf Stream.

“The region from Cape Hatteras to the Keys is part of their southern feeding range, but they tend to stay well offshore,” he said. “The tagging research has taught us they are a common winter time visitor to Florida waters.”

Hueter said he hopes Sable sends more pings in the coming weeks and months.

“Keep an eye on Sable. I might predict she may continue down the coast and wrap around into the Gulf of Mexico. We should learn a lot because she has a 5-year tag on her.”