The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued an El Niño advisory on Thursday, announcing the arrival of the climatic condition. It may not quite be like the others.

With the observed warming of the equatorial Pacific waters, there’s a 56% chance it will be considered strong and a 25% chance it reaches “supersized” levels, said climate scientist Michelle L’Heureux, head of NOAA’s El Niño/La Niña forecast office.

“If this El Niño tips into the largest class of events... it will be the shortest recurrence time in the historical record,” said Kim Cobb, a climate scientist at Brown University.

Such a short gap between El Niño leaves communities with less time to recover from damages to infrastructure, agriculture, and ecosystems like coral reefs.

Get South Florida local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC South Florida newsletters.

Usually, an El Niño limits hurricane activity in the Atlantic basin and would give relief to coastal areas in the Atlantic and Gulf Coast states of the United States, Central America and the Caribbean.

But this time, forecasters are split on whether that will come to fruition or not due to anomalously warm sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic. These pre-existing conditions would counteract the El Niño winds that normally impede storm development.

Hurricanes strengthen and grow when they travel over warm seawater, and the tropical regions of the Atlantic Ocean are “exceptionally warm," said Kristopher Karnauskas, associate professor at the University of Colorado Boulder. For the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, NOAA and others are predicting near-average activity.

In the past, a strong El Niño has led to record global warmth, like in 2016 and 1998. Scientists earlier this year had been saying next year is more likely to set a record heat, especially because El Niño usually reach peak power in winter. But this El Niño evolved earlier than normal.

In Florida, while much of the discussion about El Niño pertains to the long hurricane season, it is likely to touch the state in other ways when the storm season is over.

Traditionally, the phenomenon is responsible for an increase in wintertime showers, storms and more robust, severe weather events across Central and South Florida. Additionally, winters trend warmer than average in this scenario.

“The onset of El Niño has implications for placing 2023 in the running for warmest year on record when combined with climate-warming background,” said University of Georgia meteorology professor Marshall Shepherd.

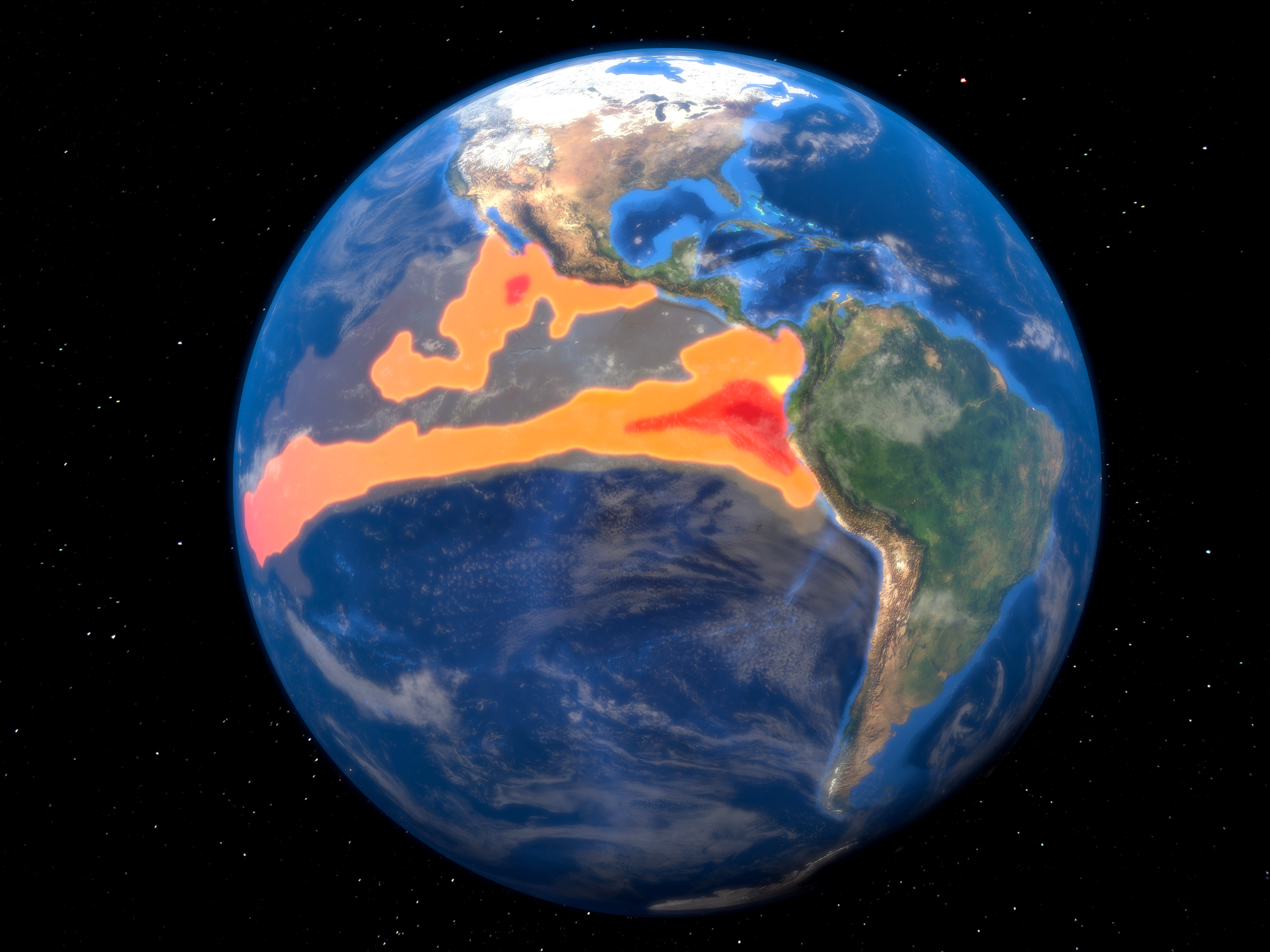

An El Niño is a natural, temporary and occasional warming of part of the Pacific that shifts weather patterns across the globe, often by moving the airborne paths for storms. The world earlier this year got out of an unusually long-lasting and strong La Niña — El Niño’s flip side with cooling — that exacerbated drought in the U.S. West and augmented Atlantic hurricane season.

What this in some ways means is that some of the wild weather of the past three years – such as drought in places – will flip the opposite way.

“If you’ve been suffering three years of a profound drought like in South America, then a tilt toward wet might be a welcome to development,” L’Heureux said. “You don’t want flooding, but certainly there are portions of the world that may benefit from the onset of El Niño.”

For the next few months, during the northern summer, El Niño will most be felt in the Southern Hemisphere with “minimal impacts” in North America, L’Heureux said.

El Niño strongly tilts Australia toward drier and warmer conditions with northern South America — Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela — likely to be drier and Southeast Argentina and parts of Chile likely to be wetter, she said. India and Indonesia also tend to be dry through August in El Niños.

While traditionally El Niño means fewer hurricanes in the Atlantic, it often means more tropical cyclones in the Pacific, L’Heureux said.

El Niño hits hardest in December through February, shifting the winter storm track farther south to the equator. The entire southern third to half of the United States, including California, is likely to be wetter in El Niño. For years, California was looking for El Niño rain relief from a decades long megadrought, but this winter’s seemingly endless atmospheric rivers made it no longer needed, she said.

The U.S. Pacific Northwest and parts of the Ohio Valley can go dry and warm, L’Heureux said.

Some of the biggest effects are likely to be seen in a hotter and drier Indonesia and adjacent parts of Asia, L’Heureux said. Also look for parts of southern Africa to go dry.

On the other hand, drought-stricken countries in northeast Africa will welcome beneficial rainfall after enduring drought conditions for several years due to prolonged La Niña events, said Azhar Ehsan, associate research scientist at Columbia University.

Some economic studies have shown that La Niña causes more damages in the United States and globally than El Niño.

One 2017 study in an economic journal found El Niño has a “growth-enhancing effect” on the economies of the United States and Europe, while it was costly for Australia, Chile, Indonesia, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Africa.

But a recent study says El Niño is far more expensive globally than previously thought, putting damage estimates in the trillions of dollars. The World Bank estimated that the 1997-1998 El Niño cost governments $45 billion.

The United States also faces hazards from El Niño despite some benefits. Ehsan noted that the increased rainfall in California, Oregon, and Washington heightens the risk of landslides and flash flooding in these areas. “While El Niño brings benefits in terms of water resource recharge, it poses certain hazards that need to be considered and managed,” he added.