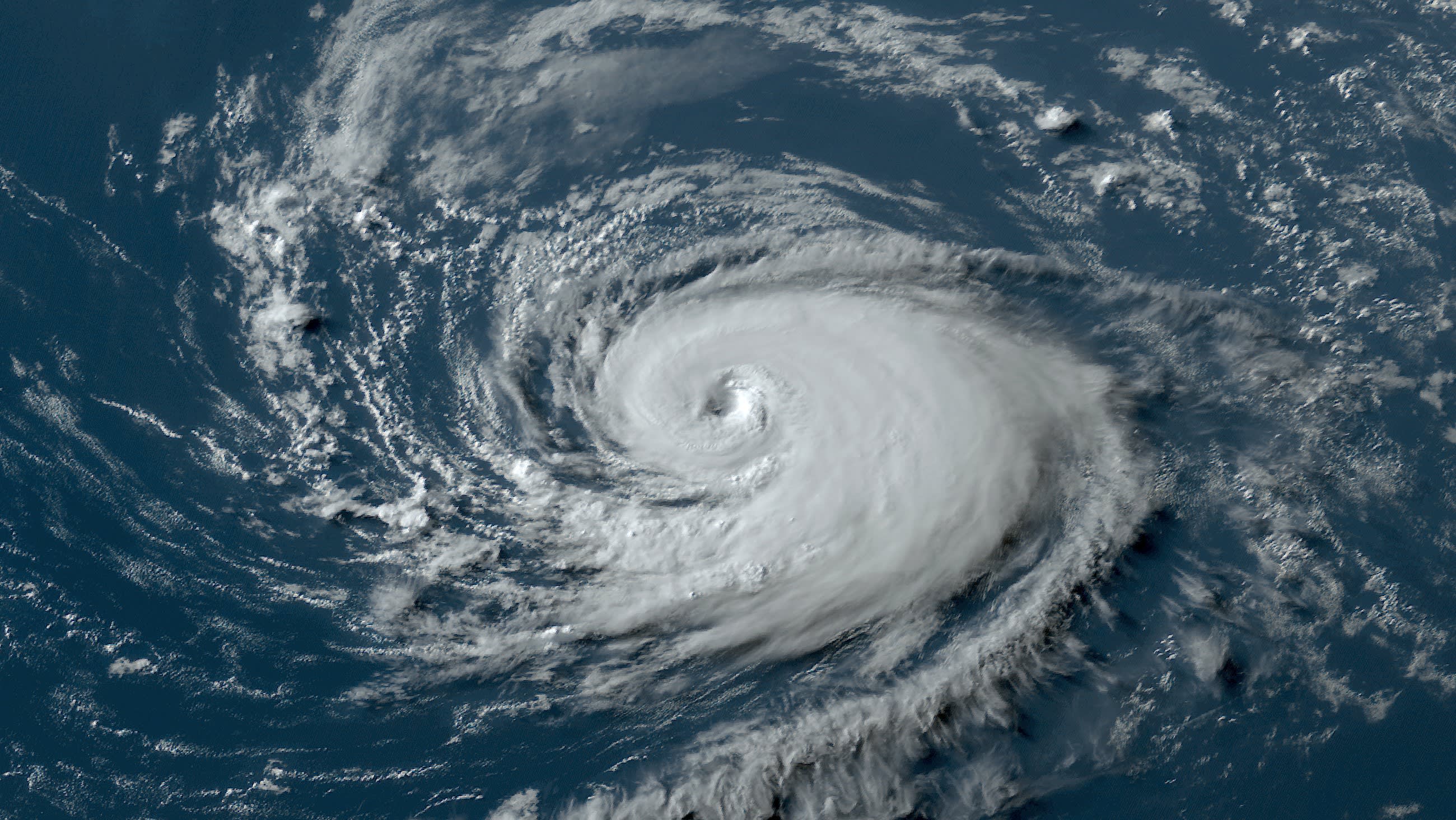

We have had a very active Atlantic hurricane season this year. Record hot sea surface temperatures have already driven the storm count past the yearly average (14), with a good chunk of the season still ahead.

I’ve had many people in Miami and Puerto Rico ask, “if it’s been so busy, how come we haven’t had any impacts, or even a significant threat? How come ‘all’ the hurricanes are turning out into the North Atlantic?”

It is time we talk about the deflector shield, or in this year’s case, shields (plural).

The shields have been “activated” this year. The east coast of the U.S., the Leeward and Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico all have been mostly protected from tropical storms, even in this very busy 2023 season.

Get South Florida local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC South Florida newsletters.

You’ve heard me talk about the “deflector shield” on television from time to time. It’s the term I’ve coined to describe a semipersistent dip in the jet stream positioned along the Eastern Seaboard. Occasionally this summer it’s been a little further east in the western Atlantic, and sometimes a little closer to the Midwest. Other times it’s been replaced by the opposite—a ridge of high pressure.

But times in which high pressure has been strong in the west Atlantic have been few and far between this year. The Bermuda high, typically a consistently strong summer feature, has also been weak.

Dips in the jet stream, known as troughs, have eroded the strength of the high pressure systems by driving cold fronts much further south than you’d expect in the height of summer. You can see the weakness of the highs compared to the June to August normal in the areas shaded in blue in the image below. This condition persists even as we now transition to fall.

June to August geopotential height anomalies at 500 millibars, courtesy Columbia Climate School International Research Institute for Climate and Society.

Hurricane Season

The NBC 6 First Alert Weather team guides you through hurricane season

If the Bermuda high had been strong and ridging into the Mid Atlantic this summer, hurricanes would have been guided westward more often, increasing the chance of getting a direct hit in places like Miami and Puerto Rico. If high pressure had been strong in the Midwest, Northeast and/or Mid Atlantic, more hurricanes would’ve been “trapped” and made their way onto other parts of the east coast.

To what do we owe such good fortune (so far)? It’s a short-term climate variation known as the Atlantic Oscillation (AO). This year, the AO index has been negative each month since June. When the AO is in negative phase, the jet stream is wavier and shifts towards the equator, and lower-than-average barometric pressures, or weaker highs, are observed over the Atlantic Ocean.

That’s why every 2023 storm except Bret and Harold have curved north. That’s 13 out of 15 tropical cyclones turning north, many of them well before they could threaten any populated regions.

A north turn isn’t always good, obviously.

That’s what happened with Idalia, which was brought straight north out of the western Caribbean into Florida’s Big Bend. It’s also what happened with Franklin, which took a 90-degree turn to hit the Dominican Republic with flooding rains. Lee’s north turn also took it to Canada’s easternmost provinces, which nose out well into the Atlantic.

Despite these notable exceptions, the deflector shields have spared most from the feared Cape Verde hurricanes in 2023. The new tropical wave emerging off Africa this week is very likely to turn northbound before ever threatening the United States. And while chances are good, it’s too soon to definitively tell whether it will do so before threatening the Caribbean.

With October just around the corner, a continuation of this pattern could enhance late-season (non-Cape Verde) threats coming from the south for locations such as Greater Antilles, the Bahamas, Florida, and the Gulf Coast.

The season is far from over. But if water temperatures were going to be record hot, I’m sure glad our shields were “on”.

John Morales is NBC6's hurricane specialist.