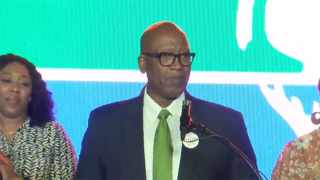

Thirty years ago, Ken Welch's father sought unsuccessfully to become the first Black mayor of St. Petersburg, Florida. Welch wore his dad's campaign button Tuesday when he claimed a resounding victory for the top office in the once-segregated city.

Welch recognized his milestone in a speech to supporters after easily defeating Republican Robert Blackmon in a city that is almost 70% white. But he said his victory is only the beginning.

“For me, making history without making a positive impact is an empty achievement,” Welch said. “Our election victory must be followed by a purposeful agenda of accountability and intentional equity for our entire community.”

Beneath its sunny exterior and tourist-friendly beaches, the St. Petersburg area has a troubled history of segregation, including racial unrest in 1996 after police fatally shot an unarmed Black man during a traffic stop.

Get South Florida local news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC South Florida newsletters.

The victory party Tuesday was held at the Woodson African American Museum of Florida, which commemorates events in St. Petersburg's racial history such as the ultimately successful 1958 effort by eight Black people to gain entry to the Spa Pool and Spa Beach that had allowed only white patrons.

Until the late 1960s, Black police officers in St. Petersburg could only patrol Black neighborhoods and had no authority to arrest whites. That changed when the “Courageous 12,” a group of Black officers, successfully sued to gain the same powers as their white counterparts.

The green benches that once famously lined the city's sidewalks were popular, but off-limits to Black people until St. Petersburg leaders removed them in the 1960s, not for racial reasons but because they wanted a more youthful image than elderly people sitting there.

Local

“What green benches meant to me was racism. It meant, ‘you're not good enough,'” said Eula Mae Mitchell Perry, a docent at the Woodson museum.

Welch also said that his father, David, was the target of death threats and racial abuse during his run for city mayor in 1991. Welch said his father's experience “taught me what real strength and courage looks like and the value of perseverance.”

As Welch spoke Tuesday night to a diverse crowd, he said, “This is what progress looks like. History is important because we must fully understand where we are coming from as a community to determine where we want to go.”

Welch, 57, is no stranger to local politics, having served five terms on the Pinellas County Commission. He was the second Black person elected to that panel.

One colleague on the commission, Janet Long, said Welch approaches issues thoughtfully, leans on facts and science and works to defuse tensions over such controversial topics such as the response to the Black Lives Matter movement and whether fluoride should be in city drinking water.

“I really appreciated how he could bring the temperature of the room down and keep us all moving forward,” said Long, who is white and a fellow Democrat. "At this place and this time in the history of St. Petersburg, he is the perfect person for the job.”

Before politics, Welch earned an accounting degree from Florida A&M University and worked in that field for several years, including for his father's firm. On Jan. 6 he will succeed Rick Kriseman, who is stepping down due to term limits.

Welch got just over 60% of the vote Tuesday, defeating Blackmon by more than 14,000 votes according to complete but unofficial results.

Blackmon, a 32-year-old member of the St. Petersburg City Council, called Welch “a good guy” after conceding defeat in what was a low-key, fairly genial contest.

“I hope all of my supporters will give (Welch) a fair shake and a fair chance,” Blackmon told the Tampa Bay Times.

Democrats won at least three of four races for St. Petersburg's city council and may win another that was extremely close Wednesday. In that race, Richie Floyd, who says he's a democratic socialist, could be the first Black person to win a district dominated in the past by whites.

Welch does not look at public service through an entirely race-oriented lens, Long said.

“He is not going to be swayed by the color of a person’s skin or where they come from or how much money they have. He is going to care about everyone because that’s just who he is,” she said.